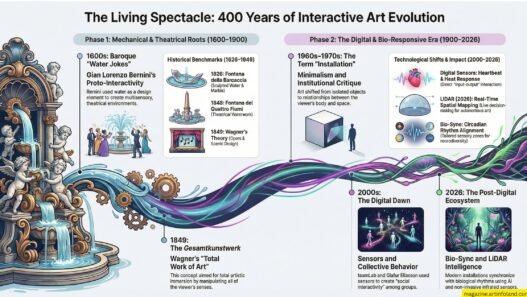

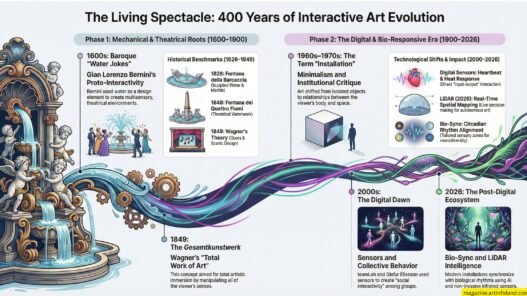

From Baroque Fountains to 2026 Light Havens: The Epic Evolution of Interactive Installation Art

In the contemporary art landscape of 2026, the term “installation” has transcended the boundaries of static objects in a room. We now inhabit “responsive ecosystems”, spaces that breathe, react, and evolve alongside the viewer. However, this high-tech immersive reality is not a modern invention; it is the culmination of a centuries-old human desire to break the “fourth wall” of art. To truly understand the Interactive Installation of 2026, we must trace its lineage back to the dramatic waterworks of the 17th century and follow the thread of sensory engagement through the ages.

I. The Genesis: Baroque Waterworks as Proto-Interactivity

The journey of interactivity begins long before the invention of electricity. In the 17th century, the Baroque period introduced the concept of art as a totalizing, theatrical experience (Gesamtkunstwerk). The masters of this era, such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini, understood that art achieved its greatest power when it engaged the viewer’s physical presence.

The grand fountains of Rome and the water gardens of Versailles were the world’s first large-scale interactive installations. These were not merely sculptures to be looked at; they were multisensory environments. The sound of rushing water, the mist on the skin, and the calculated movement of the viewer around the basin created a dynamic experience. In many Italian villas, “water jokes” (giochi d’acqua)—hidden jets that sprayed unsuspecting guests—represented the earliest form of “input-output” interactivity. The viewer’s physical movement triggered a response from the art, blurring the line between the spectator and the spectacle.

II. The Institutional Shift: From Object to Experience

For centuries following the Baroque, art retreated back into the frame and onto the pedestal. It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that the “Interactive Revolution” truly took hold. The Minimalist and Phenomenological movements of the 1960s began to argue that the “meaning” of a work of art did not reside solely in the object, but in the relationship between the object, the space, and the viewer’s body.

Artists like Robert Morris and Richard Serra created massive steel structures that forced viewers to walk through, under, and around them. This was a radical shift: the work of art was “incomplete” without the viewer’s physical navigation. In the 1970s, this evolved into “Institutional Critique,” where artists like Hans Haacke used real-time data (such as gallery visitors’ demographics) to create installations that reflected the audience back to themselves. The viewer was no longer a passive witness; they were the data points powering the art.

III. The Digital Dawn: The Rise of the Sensory-Tech Interface

The 1990s and early 2000s introduced a new tool into the curatorial toolkit: the sensor. As computing power became accessible, artists like Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and TeamLab began to create works that responded to heat, heartbeats, and motion.

A landmark moment in this era was Olafur Eliasson’s “The Weather Project” (2003) at the Tate Modern. By using humidifiers and a massive semi-circular disc of lights, Eliasson transformed the Turbine Hall into a sun-drenched landscape. Viewers responded by lying on the floor, picnic-style, interacting with their own reflections in a mirrored ceiling. This was “social interactivity”, the art didn’t just react to the individual; it created a collective behavior among strangers.

IV. The 2026 Reality: Light Havens and Responsive Ecosystems

As we navigate 2026, the “Interactive Installation” has moved into its Post-Digital phase. The novelty of “touching a wall to make it change color” has been replaced by a much more sophisticated, nuanced dialogue between the human and the machine. We are now seeing the rise of “Light Havens”, installations that combat the psychological fatigue of the 2020s through atmospheric and biological synchronization.

1. Bio-Sync Interactivity

In 2026, the most advanced installations don’t just respond to your movement; they respond to your physiology. Using non-invasive infrared sensors, installations now synchronize light pulses and sound frequencies with the collective heartbeats or circadian rhythms of the visitors in the room. This is a return to the Baroque “total experience,” but with the precision of neuroscience.

2. The “Soft” Tech Aesthetic

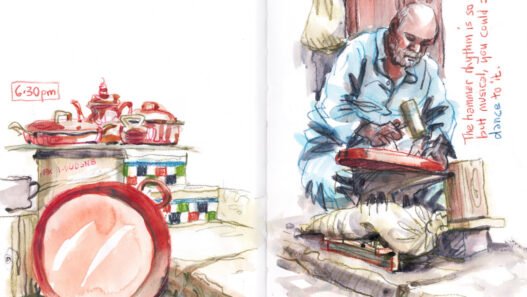

Gone are the days of visible wires and heavy projectors. 2026 installations use “Material Intelligence”, fabrics that conduct light, bioluminescent algae in glass tubes, and AR layers that are invisible to the naked eye but appear through “smart lenses.” The technology has become an “Invisible Architecture,” allowing the focus to remain on the emotional and sensory impact.

3. Neurodiversity and Multisensory Accessibility

A major achievement of 2026 curation is the focus on Neurodiverse visitors. Modern light installations now offer “Sensory Zones.” For a neurotypical visitor, the lights might be vibrant and fast-paced; for someone with sensory sensitivities, the same installation can be adjusted via a personal interface to offer a calming, tactile experience. Art is no longer “one size fits all”; it is a customized, interactive service.

V. The Professional Guide: Curating the Interactive Future

For the independent curators and artists of the Artinfoland community, the evolution of interactivity presents both a challenge and an opportunity. To succeed in the 2026 landscape, one must move beyond the “gimmick” and focus on Intentional Interactivity.

- The Narrative Over the Tech: Always ask, “Why does this need to be interactive?” If the interactivity doesn’t deepen the narrative (if it’s just for the “wow” factor), it will fail to leave a lasting impact on 2026 audiences who are highly skeptical of tech-clutter.

- The “Invisible Architecture” of Budgeting: As we discussed in our Curator Guide, interactive shows require a specialized budget. Maintenance, sensor calibration, and “on-site tech support” are now as important as insurance and crating.

- Ethics of Data: In 2026, artists must be transparent about the data they collect from viewers. If an installation “listens” to a heartbeat, how is that data stored? Ethical interactivity is a key pillar of professional practice.

The Eternal Loop of Human Presence

From the splashing fountains of the 1600s to the bioluminescent light havens of 2026, the core of installation art has remained unchanged: it is the celebration of the Human Presence. We are no longer content to look at art; we want to live within it.

The evolution of interactive art shows us that as our tools become more complex, our goals become more primal. We seek connection, reflection, and a sense of belonging within a space. For the artists and curators of today, the challenge is to use the light and technology of 2026 to create the same sense of awe and wonder that a traveler felt 400 years ago, standing before a Bernini fountain in the heart of Rome.

In the 2026 market, Interactive Art is a high-value sector. Collectors are no longer just buying “pieces”; they are buying “environments” and “experiences.” Whether you are an artist experimenting with light or a curator planning a regional biennial, remember: the most successful interactive work is the one that makes the viewer feel not just like an observer, but like an essential part of the art’s soul.