As creative retreats become more common, it’s easy to talk about access and inspiration. Questions of responsibility, authorship, and sustainability are more complex, and take longer to consider.

What creative retreats rarely ask

Creative retreats are everywhere. Most promise some form of escape – a pause from daily pressures, a change of scene, a burst of inspiration. What they rarely pause to ask is something more fundamental:

Who actually shapes the conditions in which creative work takes place?

In places with long-established creative ecosystems, this matters. Creative life doesn’t exist in isolation. It grows out of patterns of labour, informal networks, and ways of working that have developed over time, often quietly, and largely out of view.

When artists enter these contexts briefly, the challenge is rarely a lack of inspiration. More often, it’s knowing how to engage without simplifying what’s already there, or treating place as a backdrop rather than a living system.

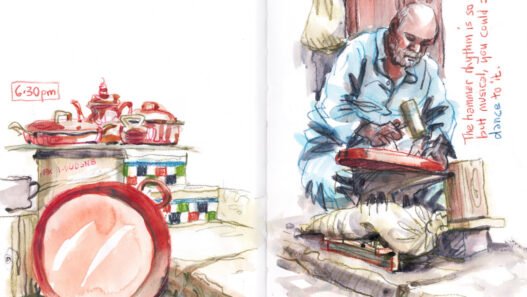

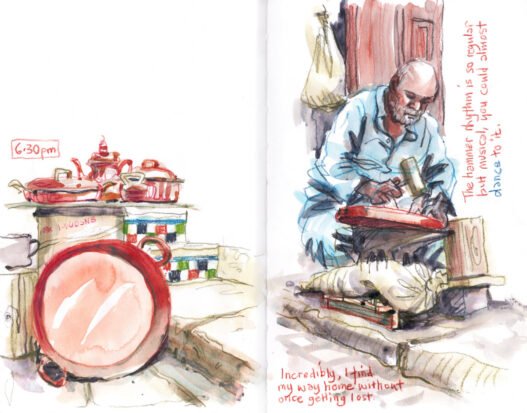

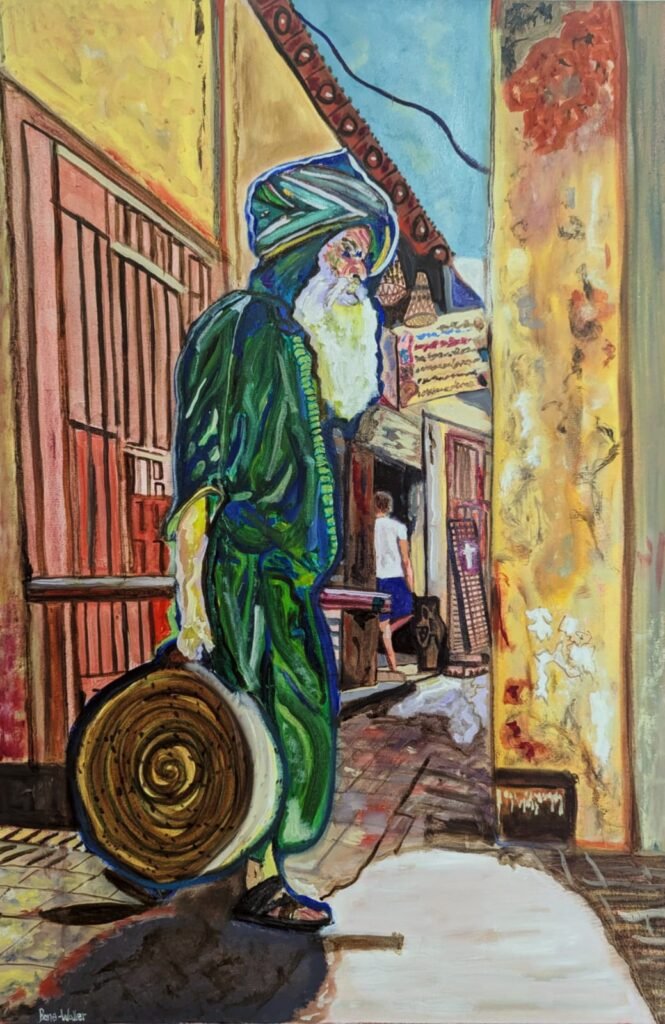

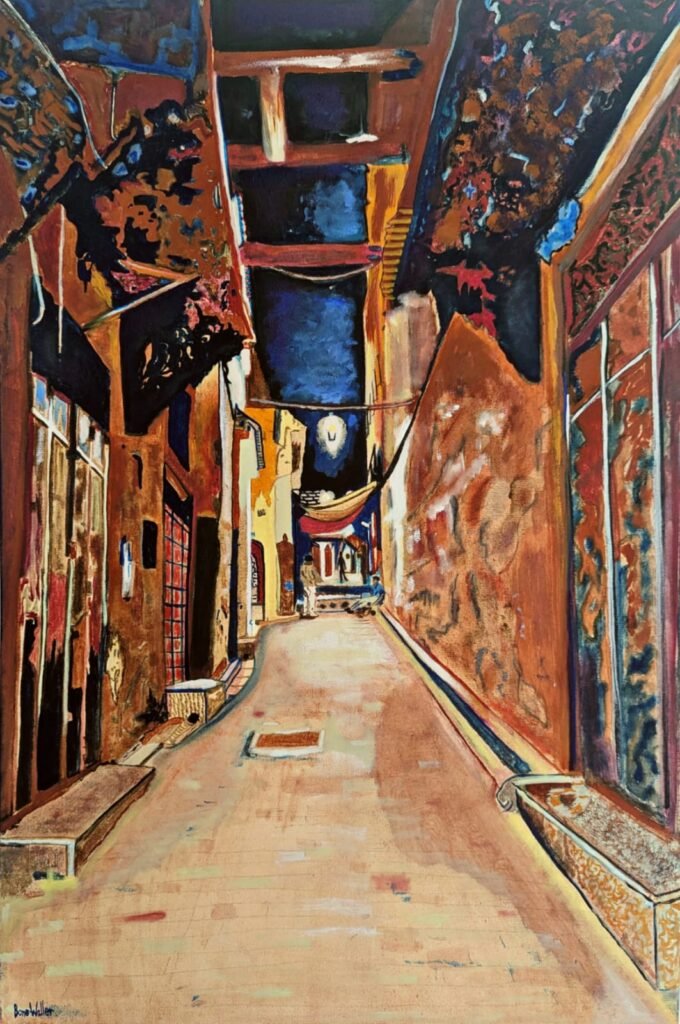

In Fez Medina, one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited artisan cities, this becomes apparent very quickly. Many artists arrive at moments of transition, between projects, places, or ways of working. Fez doesn’t rush to meet expectations, and it doesn’t explain itself easily.

Creative life in the Medina isn’t staged for visitors.

It unfolds through daily routines, long-established artisan practices, and informal systems of work that take time to notice, and even longer to become part of.

Entering Fez as a creative practitioner

Arriving in Fez for the first time can feel intense.

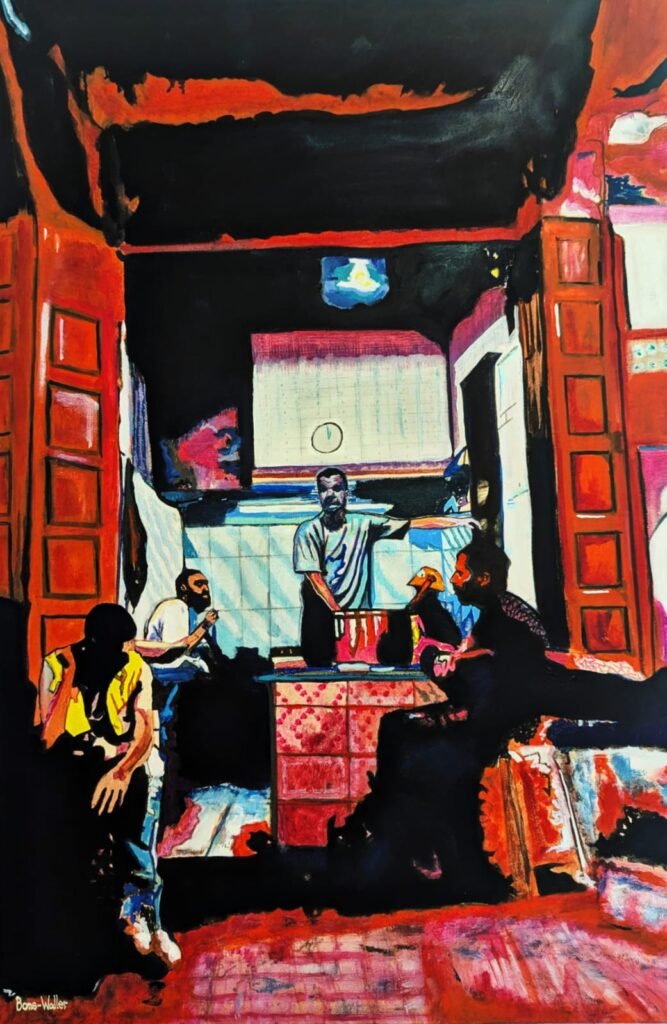

Unlike many artist retreats in Morocco, the Medina doesn’t organise itself around visitors. There are no clear markers of where creative work begins or ends, and artisans often work behind unmarked doors, indistinguishable from the surrounding homes.

Creative labour takes place alongside everyday life. Workshops, homes, shops, and informal networks overlap, and much of what matters happens through relationships rather than schedules or formal structures.

As Peter Cornish, Programme Director at Fez Art Residency (FAR), puts it:

“Fez tends to reward artists who are comfortable not knowing straight away what the experience will lead to. Openness and attentiveness matter more than certainty.”

That understanding shaped FAR’s approach from the outset.

Rather than trying to simplify the Medina or translate it into a familiar retreat model, the focus was on creating ways for artists to enter the city carefully, with time to observe, listen, and find their own points of connection.

Designing frameworks: Fez Art Residency

Rather than imposing fixed programmes or working toward predefined outcomes, FAR developed flexible frameworks shaped by how Fez actually functions, and by how artists tend to work once they arrive.

The intention wasn’t to create a new model, but to design structures that could respond to different practices, expectations, and stages of readiness.

Over time, a clear pattern began to emerge.

Artists were asking similar questions – how to make first contact with a place, how to understand who their work was for, how to respond meaningfully to context, how to sustain engagement beyond a short stay, and how to think about continuity over time.

Internally, this thinking emerged as the CARES framework – Contact, Audience, Response, Engagement, and Sustainability – not used as a checklist or a set of instructions, but as a way of thinking through responsibility at different stages of practice.

From this, two distinct pathways took shape: the Artist Immersion Week and the Host a Retreat programme.

Alongside longer-term residencies, they offer different ways of working with the Medina, depending on an artist’s readiness, intent, and willingness to take on responsibility.

Artist Immersion Week: context before outcome

The Artist Immersion Week is deliberately light in structure. It’s designed as an entry point rather than a programme to complete – a way for artists and creative practitioners to spend time in the Medina without pressure to perform, produce, or explain themselves.

There is no fixed programme to follow. No expectation to produce work. No requirement to justify outcomes.

Instead, the week unfolds through encounters with artisans, visits to cultural spaces, and exposure to everyday life in the Medina. Alongside this, participants are given space to explore independently, reflect, and move at their own pace.

What’s offered is context rather than instruction, and introductions rather than assignments. The emphasis is on attentiveness, on listening first, observing closely, and allowing understanding to develop before action.

For some artists, the week stands on its own.

It becomes a pause, a recalibration, or a chance to gain perspective at a moment of transition. For others, it helps clarify whether a longer relationship with the city makes sense.

As Cornish has noted, the intention is to respect uncertainty.

Not every artist arrives with a plan, and not every visit needs to lead to a defined outcome. Sometimes, the most valuable thing is simply time to look, listen, and decide what might come next.

From immersion to leadership: Host a Retreat

As FAR’s work developed, a different kind of conversation began to emerge.

Artists who had already spent time in Fez – through residencies, immersion weeks, or informal stays – started asking whether they could return not only on their own, but with their communities.

They wanted to bring collaborators and peers who already trusted their work, and to share Fez not as visitors, but as hosts. The idea wasn’t to reproduce a standard retreat format, but to design experiences shaped by their own ways of working, their values, and the relationships they had already built.

What became clear was a shift in how audience was understood. Not as numbers or reach, but as real people with shared expectations, existing trust, and a sense of responsibility on both sides.

Alongside this came a practical question.

How could these relationships be deepened in a way that remained both authentic to their work, and at the same time remain financially viable?

Host a Retreat emerged as a response to that question.

A broader shift beneath the programmes

Over time, something consistent began to surface across both pathways. The questions artists were asking pointed to a wider shift in how many are now viewing their professional lives.

Increasingly, artists are not only focused on making work.

They are also thinking about the contexts in which that work is shared – designing experiences, gathering communities, and taking responsibility for how creative activity is framed and sustained.

Seen this way, growth is less about scale or commercialisation and more about authorship and care. It’s about creating safe space for others, working ethically within a place, and finding ways to build financial continuity through relationships rather than institutional funding.

Retreats as community-led practice

Host a Retreat is built around collaboration, but it’s also shaped by a clear sense of responsibility.

Hosting, in this context, isn’t treated as a one-off event. It’s understood as a form of sustained engagement – a relationship that strengthens before, during, and after the retreat itself.

Rather than framing retreats simply as creative gatherings, the programme supports artist-led initiatives that grow out of existing trust, reputation, and relationships.

Seen this way, entrepreneurship becomes less about business models and more an extension of artistic authorship, and how artists organise, share, and sustain their work.

Rather than providing a pre-packaged experience, retreat leaders create retreats that reflect their own practices, values, and ways of working.

Artists design, communicate, and lead their programmes themselves, while FAR supports the practical foundations – accommodation, logistics, cultural guidance, and on-the-ground support – so that attention can remain on the work and the community around it.

As Cornish points out, this reflects a shift already underway in many artistic practices:

“For many artists, hosting a retreat grows naturally out of their work. It brings communities together in a more intentional way, and creates income through relationships rather than institutions.”

This isn’t incidental.

It speaks to a broader reality within the contemporary arts, where sustaining a practice increasingly depends on an artist’s ability to design, communicate, and support their own initiatives.

Sustainability here is measured less by scale, and more by continuity – financial, relational, and professional – over time.

Choice, readiness, and responsibility

Although they serve different purposes, the Artist Immersion Week and Host a Retreat are grounded in the same set of values. Both prioritise slowing down, placing context before consumption, and allowing agency to guide decisions rather than imposing a path.

What connects them is an underlying logic – beginning with contact, moving through questions of audience and response, deepening into engagement, and only then raising issues of sustainability.

Responsibility, in this sense, isn’t assumed at the outset. It’s something that may emerge, or not, and allows artists to decide how, and whether, they want to take it on

The Immersion Week allows artists to arrive without pressure. It offers time to observe carefully, to pay attention, and to decide what kind of relationship, if any, they want with Fez.

Host a Retreat, by contrast, is for artists who feel ready to take on something bigger.

It involves shaping experiences for others and taking responsibility for how creativity, logistics, and finances intersect. The emphasis isn’t on progression, but on readiness.

There’s no expectation that one pathway leads naturally to the other. What matters is that both respect timing, choice, and the realities of artistic practice.

FAR doesn’t promise transformation, and it doesn’t encourage ambition for its own sake. It offers conditions, and leaves a door open for artists to decide how deeply they want to engage.

In a city where artisan knowledge and entrepreneurship have coexisted for centuries, this approach feels fitting.

What emerges is not a model to replicate, but a way of working that values care, continuity, and the long view, and where responsibility is something an artist can step into thoughtfully, or choose not to at all.

This article is an editorial feature in collaboration with Fez Art Residency

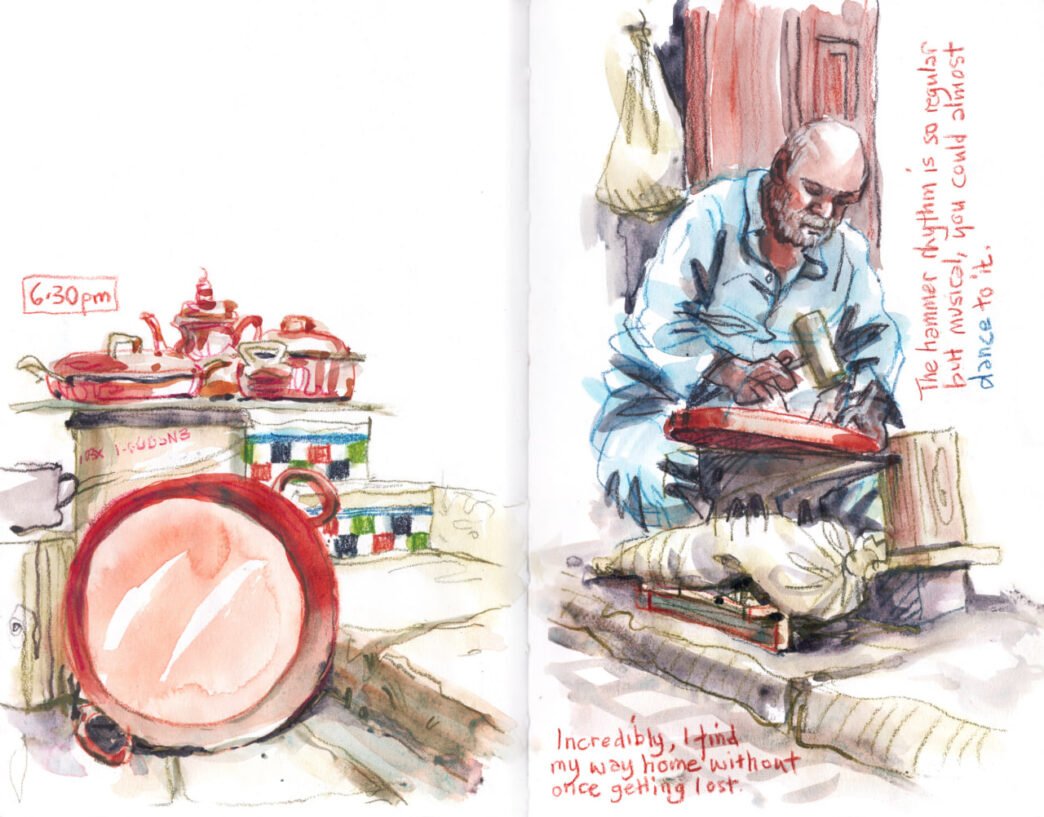

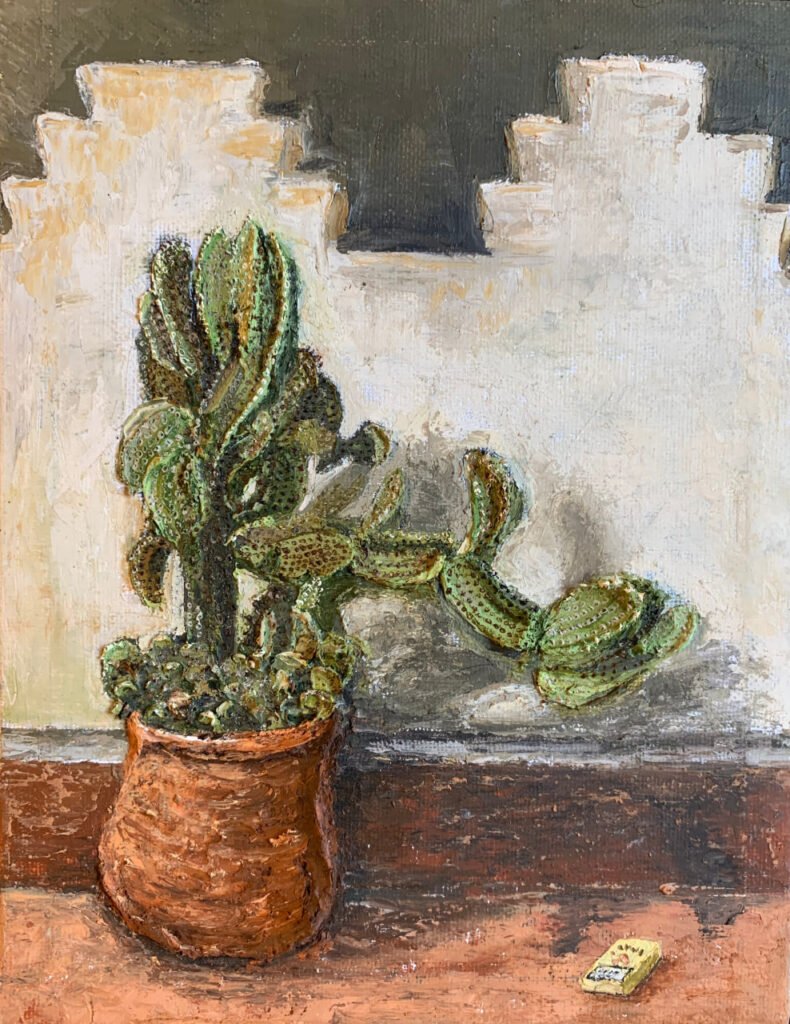

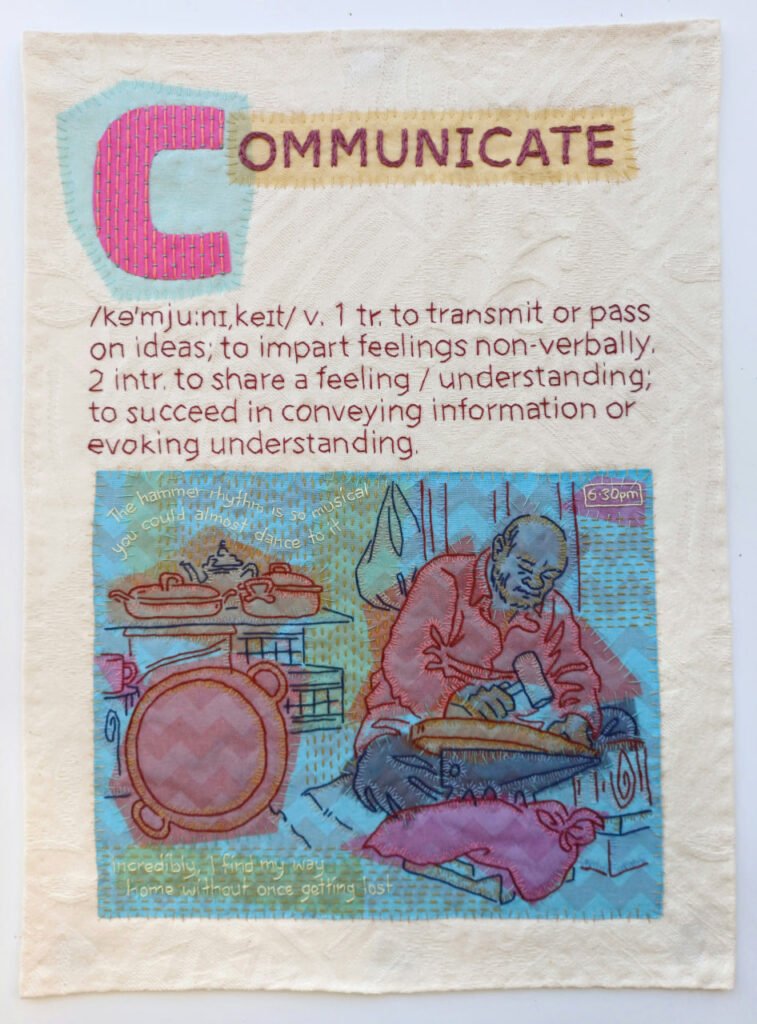

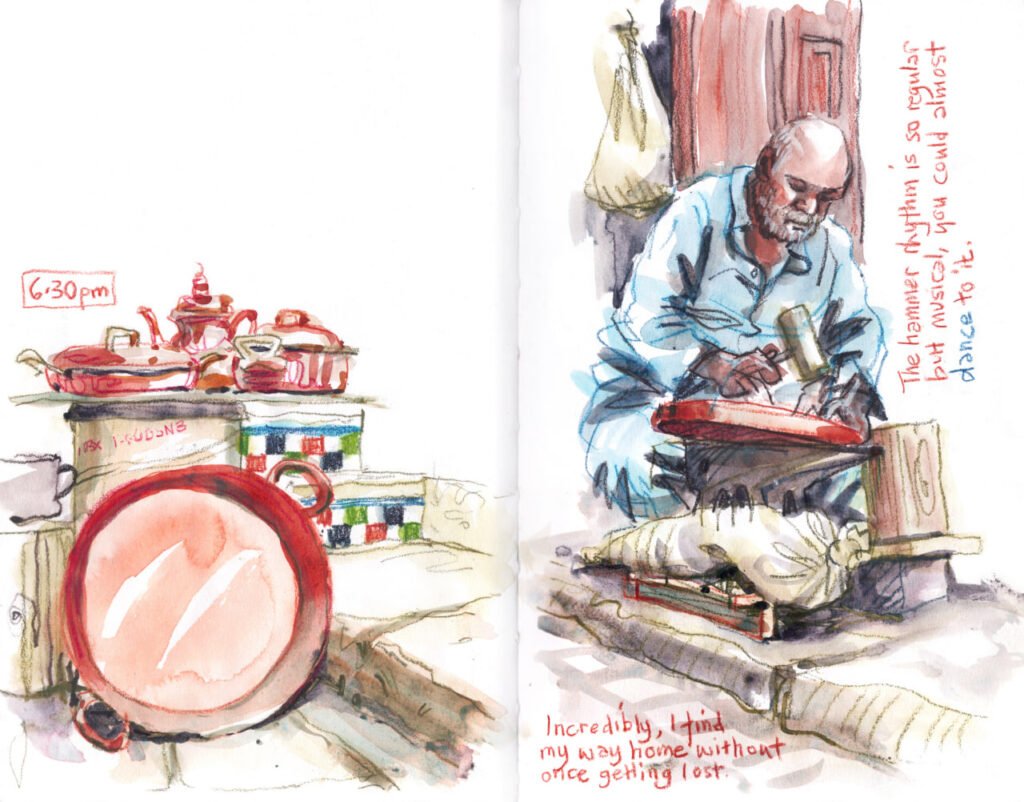

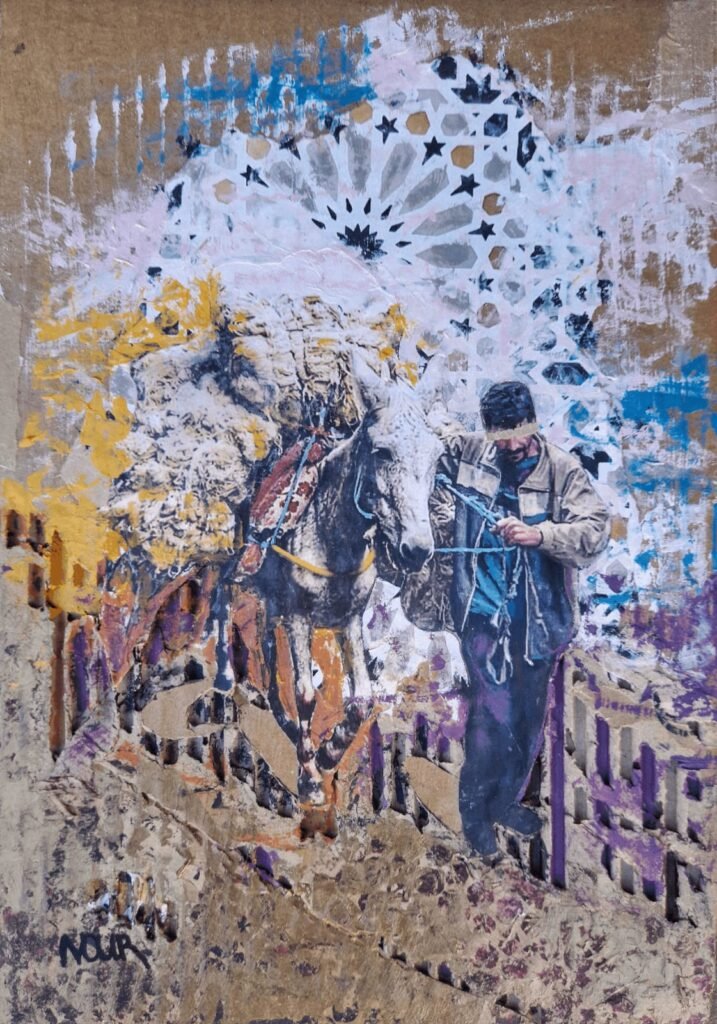

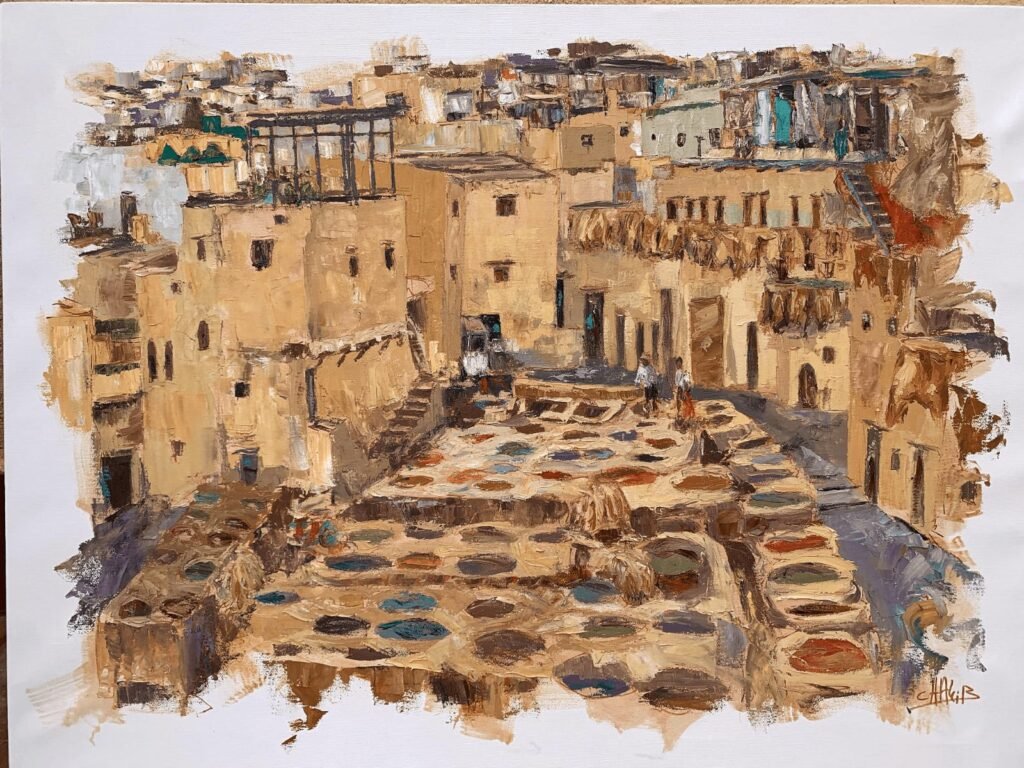

All illustrations are credited to artists who have stayed with Fez Art Residency and are included here with gratitude and thanks.

Details of the Artist Immersion Week and Host a Retreat programme can be found on the Fez Art Residency website. Questions can be directed to connect@fezartresidency.com